The high-profile murder investigation of South African rapper AKA (Kiernan Forbes) has once again cast a shadow over the country’s policing hierarchy, this time revealing sharp internal divisions at the highest levels of the South African Police Service (SAPS).

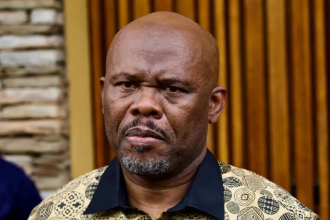

Suspended Deputy National Police Commissioner for Crime Detection, Lieutenant General Shadrack Sibiya, has told Parliament’s Ad Hoc Committee that the handling of the case triggered a tense standoff between him and KwaZulu-Natal Police Commissioner Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi.

Testifying under oath, Sibiya said the friction began when the then police minister Bheki Cele requested an update on the investigation. Instead of contacting Mkhwanazi directly, Sibiya said he reached out to the KZN commissioner’s deputy for information. The move, he admitted, may have been interpreted as undermining Mkhwanazi’s authority.

“I got a call from him, and he said, ‘You are not going to phone my province and order my people around,’” Sibiya recounted. “I did not take kindly to his reaction.”

According to Sibiya, the matter escalated until both Cele and National Police Commissioner General Fannie Masemola convened a meeting to mediate. Sibiya described the sit-down as professional and amicable. “It was a mature meeting. There was no fight. We shook hands and saluted each other as we left,” he told the committee.

Despite that reconciliation, the truce didn’t last. Sibiya said he was blindsided when, on the eve of Mkhwanazi’s 4 July press conference, the KZN commissioner publicly accused him of being central to the disbanding of the Political Killings Task Team (PKTT)—a move that Mkhwanazi argued weakened investigations into politically motivated murders, particularly in KwaZulu-Natal.

Mkhwanazi claimed that Sibiya ignored a warning from Masemola, who had raised concerns about a directive issued in December 2024 by the then police minister Senzo Mchunu, instructing structural changes to specialised units.

Sibiya, however, defended his position before Parliament. He argued that the PKTT, while active in KwaZulu-Natal, was not a formally established unit within the SAPS hierarchy. “When I look at the PKTT as a task team mainly focused on KZN, it’s a cause for concern,” he said. “We have other political killings throughout the country not being tended to by the PKTT.”

He further explained that, based on guidance from General Masemola, the task team was regarded as a temporary operational structure, not a permanent one. “I was therefore of the view that the commissioner did not see the task team as a formal unit,” Sibiya added.

The PKTT was originally set up to investigate political assassinations in KwaZulu-Natal, a province long plagued by violence linked to political rivalries, local government disputes, and tender-related conflicts. Its reported disbandment has sparked national debate over whether the SAPS is adequately resourced—or willing—to tackle politically motivated crimes beyond KZN’s borders.

The tensions between Sibiya and Mkhwanazi have exposed deep fractures within the country’s top policing ranks, at a time when public confidence in law enforcement remains fragile.

Sibiya insisted that despite the differences, his actions were guided by “organisational procedure, not politics.” Mkhwanazi, however, maintains that the timing and manner of the task team’s disbandment crippled ongoing investigations, including some linked to the assassination of AKA.

As Parliament’s committee continues to probe allegations of political interference and criminal infiltration within the police, both men’s testimonies are expected to shape the broader narrative about accountability and leadership within SAPS.

In the end, the death of one of South Africa’s most beloved artists may have done more than expose crime on the streets—it may have illuminated a power struggle behind police walls that few outside the force ever saw coming.