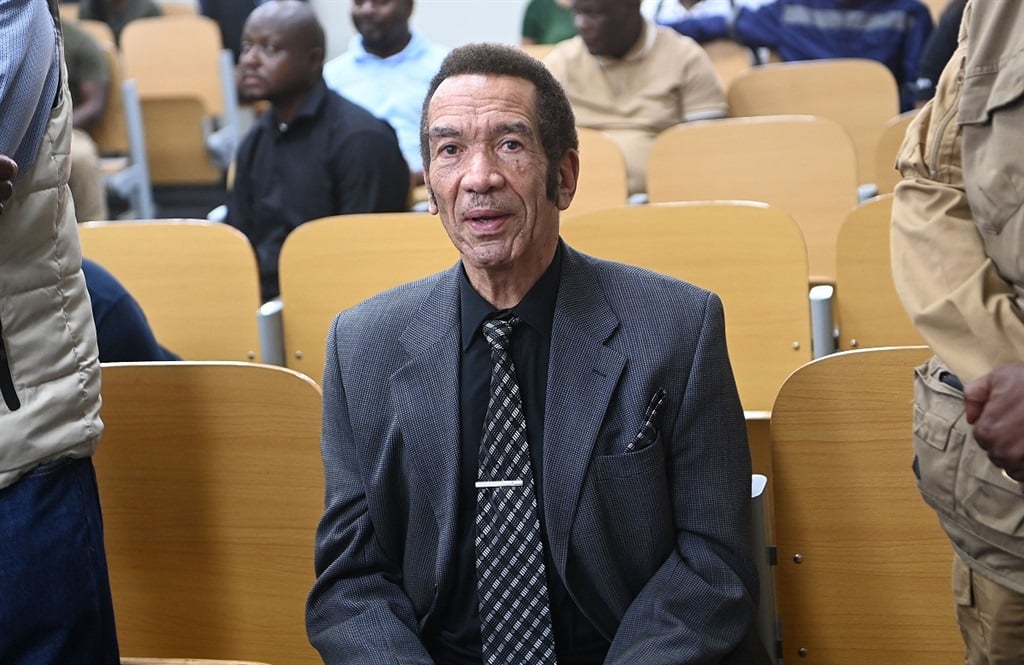

Former Botswana President Ian Khama’s decision to return to his homeland after three years in exile in South Africa has brought fresh tension to Botswana’s upcoming elections, scheduled for 30 October. Khama, who fled his country in 2021, faces multiple charges, including illegal firearms possession, money laundering, and receiving stolen property. Despite these charges, his return signals his determination to unseat his political rival, current President Mokgweetsi Masisi.

The Charges Against Khama

Khama’s exile began after serious allegations were brought against him by the government of Masisi. He feared for his safety and freedom after a series of criminal charges were laid, and arrest warrants were issued when he failed to appear in court for firearms-related cases. However, in a surprising turn, a Gaborone magistrate recently set aside these arrest warrants, allowing Khama to return without immediate risk of detention.

In an interview, Khama revealed that he returned to Botswana despite the lack of assurance he wouldn’t be arrested. He has taken measures to ensure his personal safety and remains cautious about his future, as he still needs to appear in court on 29 November to face the firearms charges.

Khama’s Political Strategy

Khama has wasted no time since his return. He is actively campaigning for the opposition Botswana Patriotic Front (BPF), a party he helped form in 2019 following his fallout with Masisi. Although he is constitutionally barred from running for president again, Khama is set on one goal: to dethrone Masisi. The BPF’s presidential candidate, Mephato Reatile, stands in his place, but Khama’s political influence remains central to the opposition’s campaign.

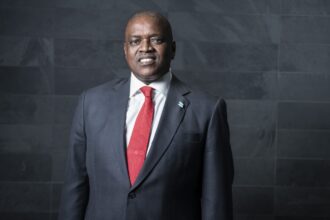

The BPF’s prospects for victory seem slim, with the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC), led by Duma Boko, being the more likely party to unseat the ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP). However, Khama’s involvement in opposition politics has rejuvenated his supporters, especially in the central regions of Botswana, where the BPF made significant gains in the 2019 elections.

A Bitter Rivalry

Once allies, Khama and Masisi’s relationship has soured significantly over the years. Khama initially supported Masisi’s succession, but soon after Masisi took office in 2018, their differences became apparent. One of the most contentious issues between the two was Masisi’s reversal of Khama’s ban on elephant hunting, a significant move for Khama, who is known for his conservationist stance.

Masisi also limited Khama’s rights and privileges as a former president, further driving a wedge between the two. Additionally, Masisi’s shift in Botswana’s foreign policy, aligning more closely with southern African liberation movements, marked a departure from Khama’s maverick approach, especially his outspoken criticism of Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe.

The BDP’s Shift and the Threat to Democracy

The BDP’s decision to join the Former Liberation Movements of Southern Africa (FLMSA) in 2019 raised eyebrows, both within Botswana and beyond. The FLMSA, largely dominated by Zimbabwe’s Zanu-PF, is an informal club of former liberation movements that have retained political power in their respective countries. Critics fear that Botswana’s participation in this group could lead to increased intolerance of domestic opposition, a concern highlighted by Jane Duncan, a professor at the University of Glasgow. She warned that the BDP might adopt the FLMSA’s tendency to label dissent as foreign-funded uprisings rather than address genuine grievances.

Political scientists in Botswana, including Professor Zibani Maundeni, share these concerns. Maundeni sees Khama’s return as a significant threat to the BDP’s dominance. The BPF’s success in the central region during the 2019 elections and its ties with the UDC have rattled the BDP. There is growing fear that Khama’s political manoeuvres could lead to an upset in the upcoming elections. This fear, Maundeni argues, may push the BDP towards undemocratic strategies to maintain power, putting Botswana’s democracy at risk.

Maundeni also suggests that the BDP’s alignment with the FLMSA will prevent Khama from receiving support from other liberation governments in the region. The intelligence services of these nations may even collaborate with the BDP to counter Khama’s political efforts. Khama’s hardline stance against Mugabe and accusations of his involvement in Zimbabwe’s 2008 insurgency further strained Botswana’s relations with its neighbours, which the BDP has worked to repair.

The Opposition’s Challenges

Despite Khama’s return and the political stir it has caused, Dr Leonard Lenna Sesa, a political science lecturer at the University of Botswana, believes that the opposition faces an uphill battle. The failure of the UDC and BPF to form a formal alliance will likely split the opposition vote, allowing Masisi and the BDP to secure another victory.

In a region where former liberation movements have clung to power for decades, Botswana’s political landscape is set for an intense battle. Whether Khama’s return will lead to a significant political shift or merely deepen the divisions remains to be seen, but the stakes are undeniably high in this year’s elections.